Interleaving Practices Thesis Front Cover (Dalziel & Jung 2022)

In 2023 I completed an art PhD, Interleaving Practices and Critical Kits at the Lancaster Institute for the Contemporary Arts through a Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS) Doctoral scholarship. It’s taken me well over a year to publish a blog post reflecting on that process after completing a residency with METAL Liverpool developing educational resources for experimenting with Bioplastic, the Algae Bioplastic Lab. In that research and thesis I employed a diverse mix of social theory grounded in the context of my art practice, to explore the intersections of socially engaged art practice, technology based ‘maker’ culture, microbiology and creative approaches to interdisciplinary education. The art practice it was grounded in was one that took the form of individual and serial workshops, funded commissions and residencies that featured working and ‘embedding’ myself with specialist technical communities like computer programmers, planespotters, radio enthusiasts, the broadly defined ‘maker culture’ and most recently, microbiologists. The embedding is primarily the form that aligns with so called ‘socially engaged art practice’, where I typically spend long periods of time, from 3 months or so to 4 or 5 years working with and alongside people in the social contexts in which they work and live. By ‘maker culture’, I mean a kind of DIY practice where people, often technically minded software and hardware professionals, hobbyists and engineers use online networks and shared workspaces known as ‘makerspaces’ to make projects, products and objects using more or less democratised open source tools for 3D printing, lasercutting and other kinds of hybrid digital and physical fabrication. Embedded in that culture, I developed an approach to interdisciplinary work in the tradition of so-called ‘socially engaged’ and also ‘art-science’ practice. This evolved into a method for art practice and creative social science I called Interleaving Practices, which was both the end result and methodology of the research.

I spent around 2-3 years observing interactions in the labs and teaching spaces of the Faculty of Health and Medicine (FHM) at Lancaster University, the makerspace DoESLiverpool (DoES) in Liverpool, and an emerging community of 3D printing enthusiasts at the Neuromuscular Centre (NMC) in Winsford, Cheshire where I continue to work today.

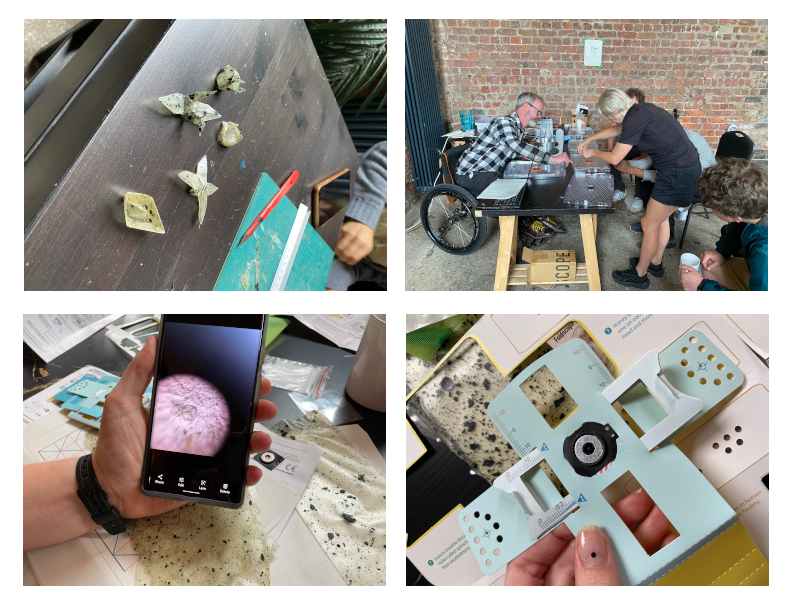

I produced a set of maker-like projects (using standard maker techniques of lasercutting and 3D printing, internet of things connectivity) that included 3D printed environments for observing and breeding fruit flies, to help people with genetic conditions understand their condition, a handheld desktop microscopy platform and kit for interacting with Euglena gracilis algae and microfluidics using the popular origami microscope, Foldscope and Biomaterials and Wearable Technology Interest group at DoESLiverpool with co-director Jackie Pease. I also made experimental DIY molecular diagnostic kits, an art & science card game, which became a series of case studies in the research. I also made various offshoot projects outside the scope of the thesis, including a project with supervisors Rod and Viv Dillon and colleague Hwa Young Jung for Domestic Science which won the Microbiology in Society 2020 award, Endosymbiotic Love Calendar.

I would explore a wide and diverse body of art-science, biological science, technology and kit making literature and practice and respond to it by making grounded in the research situations I was embedded in at DoES, FHM & the NMC. I would then observe participants using these projects and then re-make and develop the kits and projects, iterating through this process and using the observations as research data, and the kits and projects developed acted as the artworks. It’s worth noting that in my practice the artworks and art objects are de-prioritised in favour of the social activity they generate. In the thesis each project is documented on GitHub and included as a manual at the end of the bibliography, following in the footsteps of makers in DoESLiverpool and the making community.

‘Interleaved practice’ is an existing learning technique from the field of applied cognitive psychology where learning opportunities and practices are ‘spaced’ out and distributed between others, often across different subjects or types of skills or knowledge to allow for contextual learning. This is opposed to ‘blocked practice’ where learning tasks are consecutive and seperated from others, blocking other tasks until the primary task is completed or mastered. Interleaved practice has been shown to be empirically more effective in the fields of mathematics learning in children and adults. 1

Interleaving Practices as a research method, similarly argues for the benefits of this kind of learning ‘spaced’ between multiple types of activity, but extends this spacing across different kinds of practices and disciplines, even across different social relations. It’s a messy self conscious method to at once observe, analyse, participate and intervene while being grounded in a particular social process. In the context of a particular field of social science, Science and Technology Studies (STS), I made claims for it, in common with the traditions of socially engaged work, as a progressive, ethical and potentially liberatory and politicised form of creative knowledge production with an eye on social justice and change.

I’ve since developed broadly my understandings of social theory and feel able to reflect on, reconsider and contextualise my research within say, a political economy of theory and practice in the arts and social sciences. It’s revealed to me a whole multitude of critique and elaboration of much of the literature fundamental to my research and also developed the constraints to the claims of the thesis. It’s not uncommon to have completed a thesis and then realise you might disagree with some of it’s claims and conclusions, or come to reflect on or reject it’s theoretical underpinnings and that’s happened to me in some part. Interleaving can also be more simply understood in established philosophies of early modernity, such as Hegelian dialectics, something Noam Chomsky once simplified in conversation with the great dialectical biologist Richard Lewontin, as ‘thinking correctly’. But it’s also just a part of what my supervisor Rod Dillon described as coming to realise that what you know in your research, has only revealed just how much you don’t know.

The Interleaving Practitioner

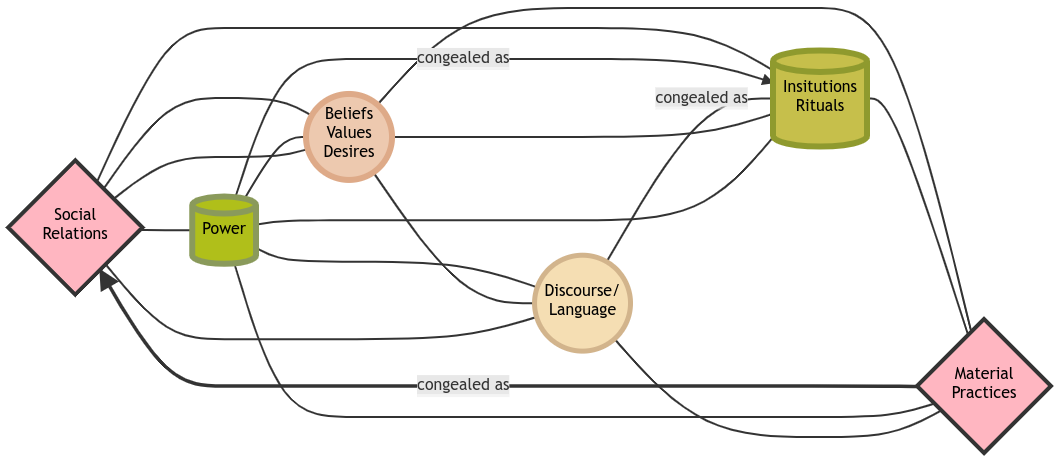

What is at the heart of the Interleaving method, to be an ‘Interleaving Practitioner’, is the very simple idea common to traditions of social science ethnography, that to engage with or analyse a complex group or thing, you may have to get close to them socially rather than review or analyse existing literature or data. I may have privileged that approach over others and since understand how ‘getting close’ to data or literature could be just as revealing as in depth ethnography, and that generalisations are not necessarily reductions, it’s a matter of choosing the strategy and tactics for what you want to find out. This ethnographic approach acknowledges that in the process of ‘getting close’ you may be changed along the way and that a study of something is not a simple observation from nowhere, but an intervention that will evolve and also potentially change what’s being studied. It starts from a position that any ‘thing’ is always an evolving social process involving practices that any kind of research or practice is part of and leads to questions of how things are done, who does them, how, where and why they do them and who benefits. David Harvey outlines a generic model for a social process in his landmark book on Geography, Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference 2 below.

The Social Process as outlined by Harvey (1996)

It’s almost banal to say that by studying something you become part of, and so can change, the very process you are studying. I think that it’s important to realise that, in order to be more accountable to what you are studying and what implications your study might, or might not, have. Interleaving Practices tries to make that explicit as a strategic method for slow ethonographic exploring of those social processes, focussing on practices, what people do. Instead of only observing and interviewing people, the standard way of doing much social science research, you also do what ‘they’ - the people carrying out the practices you are studying - do. You try to follow along with their material practices. Because much of my practice has been embedded in maker culture, you make something together with them that otherwise would not be made.

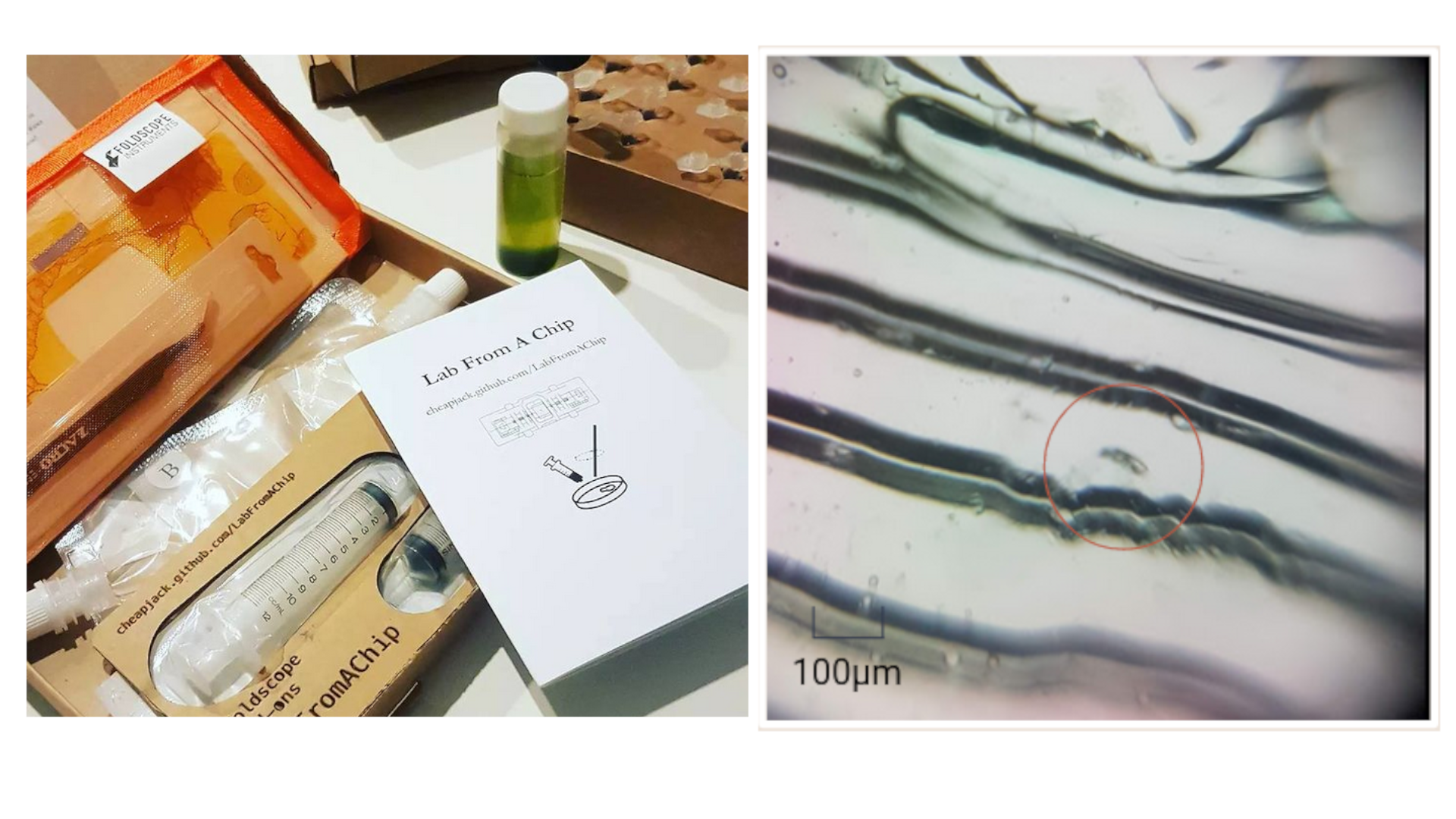

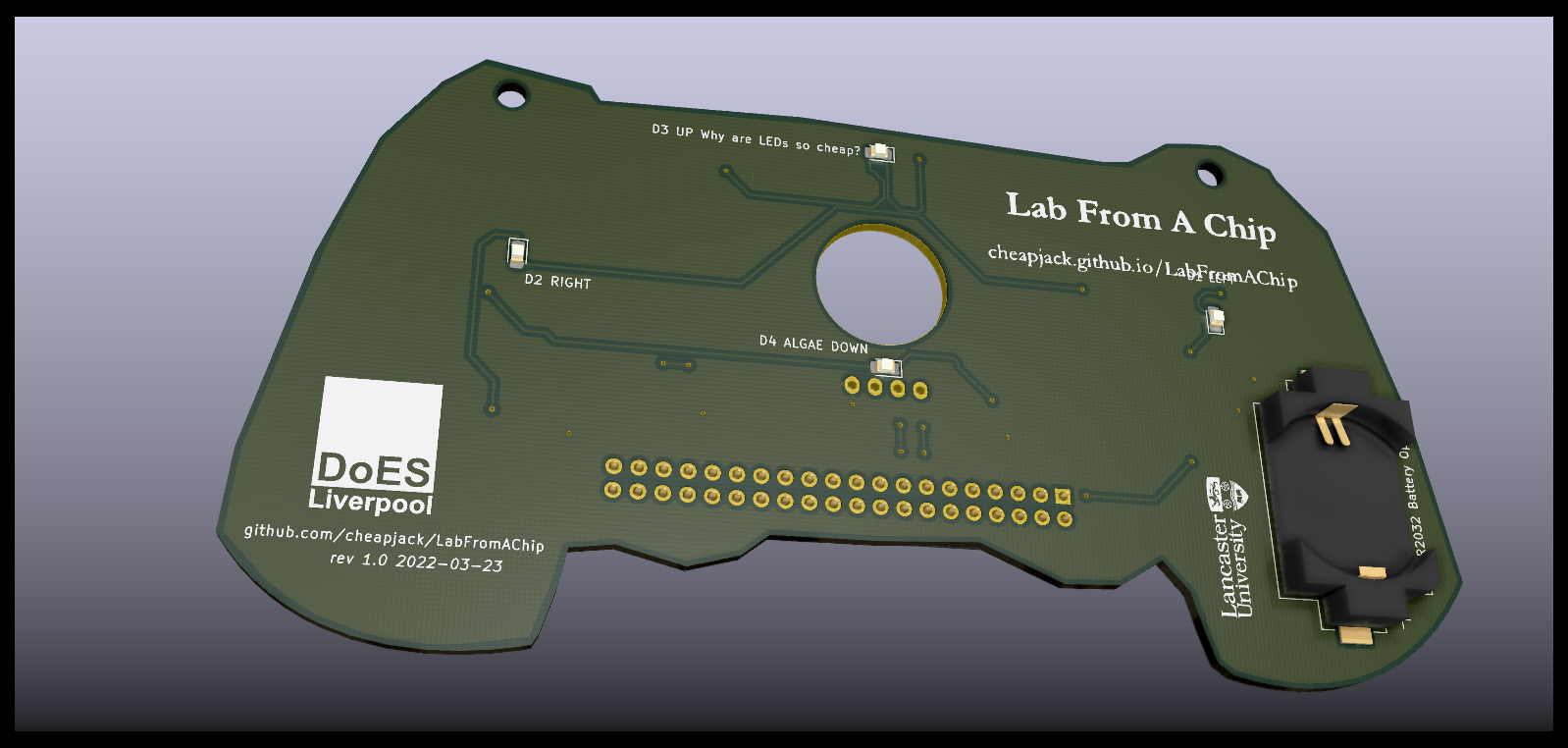

In my practice the making would lead to a prototype or project that could be used by and for the people and situations of the workshop or project to reveal to themselves and others the existing social process. The artwork is often the thing made and the social activity that goes around it, usually in the form of participatory workshops, games or events using a made object or more recently ‘kits’. Used as a method for research, the object or thing made with and for the people being studied would not only internalize all the dynamics and practices of the social process but also reveal them for analysis that long interviews and observations from a distance might not. In one of my case studies this social object was a technical kit made with the microbiologists I was studying, that could be used in a workshop setting, or posted to somebody. The LabFromAChip kit was designed for non-scientists to not only learn what microbiologists do, but to participate in simplified versions of the same practices I observed over 3 years in a busy research and teaching microbiology lab at the Faculty of Health and Medicine at Lancaster University.

LabFromAChip kit development with microscope image made from the kit

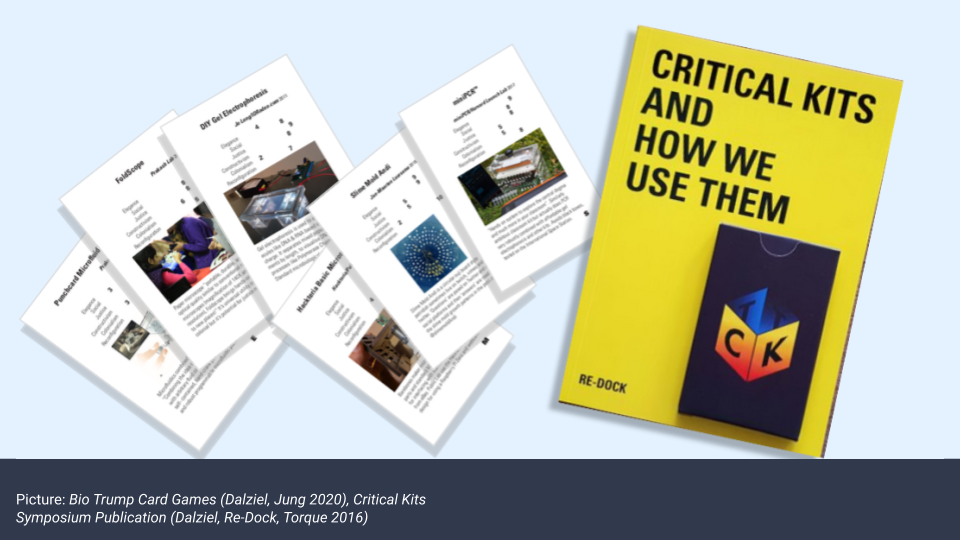

My thesis initially proposed expanding on the idea of ‘Critical kits’ a term from a symposium I organised collaboratively with artist Neil Winterburn and collective Re-Dock 3 in Liverpool in 2016 and a subsequent book, Critical Kits And How We Use Them 4 to explore the influence of maker culture on art practices in the North West of the UK. Building on the symposium, in my research I began to respond to this through forms of ‘critical making’. Critical making refers to the work of Matt Ratto, who coined the term, Garnet Hertz and others on the intersection of academia and maker culture 5.

Image of slide of Critical Kits card game and book made for the Critical Kits Symposium

By exploring how the critical making approach to kits could be used in this ethnographic mode of art practice I ended up developing an art practice as a social scientific method. To build something like a kit with people you need to get to know them and the context in which they work enough to be able to decide on something to make, something that both the researcher and the research subject share an interest in. That requires building a relationship and a kind of constant negotiation that involves a much larger amoumnt of time and a qualitively different kind of interaction and opportunity for observation and analysis than conventional interviews or ‘fly on the wall’ style ethnographic studies.

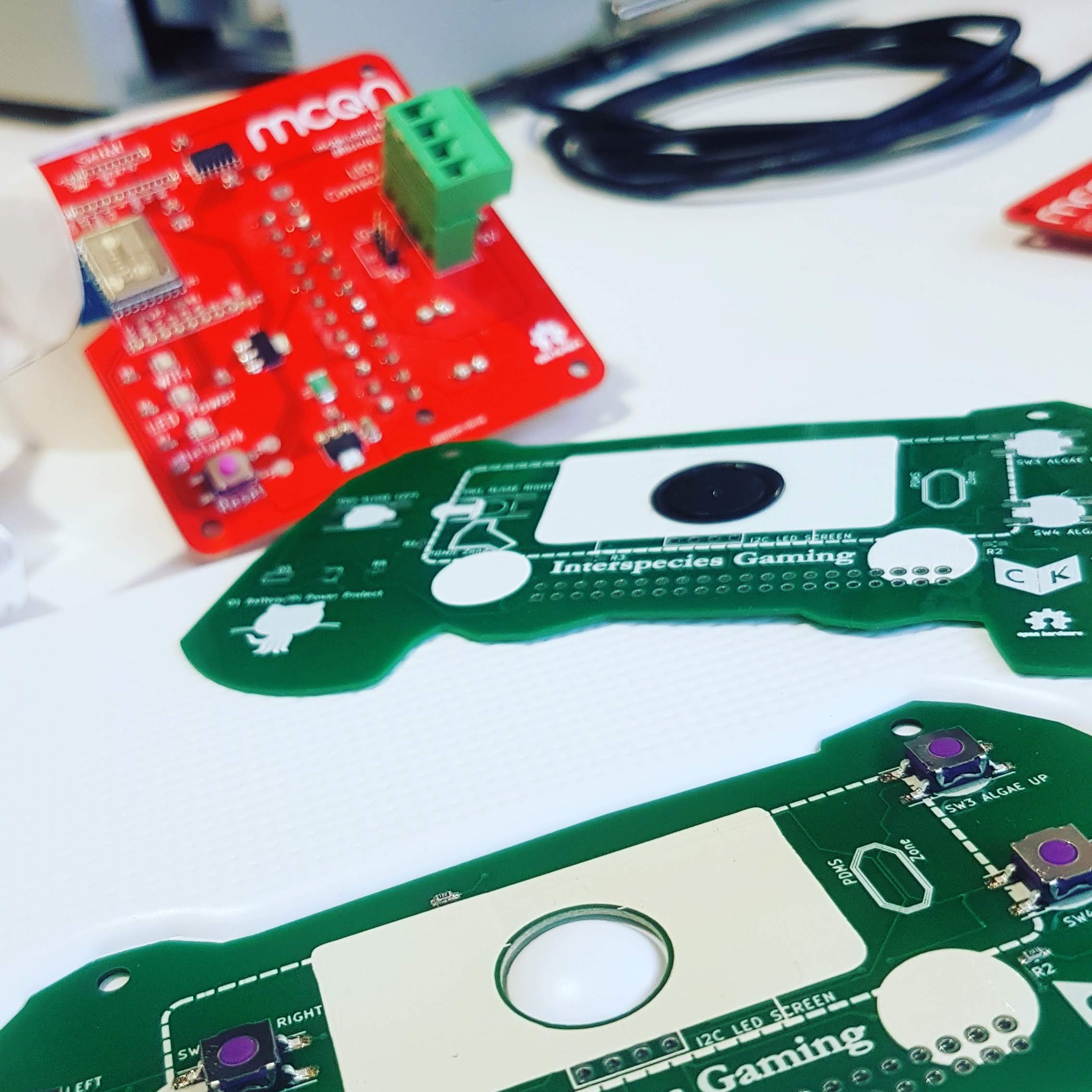

LabFromAChip PCB design rendered before fabrication in Schenzhen, China

The other key element in this kind of approach is that you can be explicit, both to yourself as a researcher and with the participants that by making together you are also constructing an analysis with them of the collaborative process. That can of course also happen when you reflect with people in a conventional interview situation. But my research explored how the slow complicated interdisciplinary embodied act of making something collaboratively, means you can develop more capacity for reflection, analysis and ultimately mutual understanding even if there is antagonism and frustration along the way. Making a technical tool or object like a kit requires lots of different practices and so alot more opportunities for building an understanding of those social processes. It meant I could collaboratively write extensive tutorials of PCB design in KiCAD with MCQN Ltd while also analysing how diverse groups of makers learn together.

Making the solder mask and soldering on components to the Interspecies gaming platform for interacting with algae once receiving printed circuit boards at DoESLiverpool alongside some product development for Internet of Things company MCQN

Along the way I used the knowledge of the makerspace DoESLiverpool, my supervisors and existing social theory, primarily science and technology studies (STS) to inform the approach. I ended up with a portable kit that allowed non-scientists and non-makers to follow some of the material practices that I observed in the Faculty of Health and Medicine and also the makerspace, like making microscopic environments to observe algae, in the Lab From A Chip project. The kit embodied and internalized the dynamics of makerspaces and biology labs, the dependence on globalised ‘just-in-time’ supply chains, how they worked across disciplines and scales, their political commmitments, the history of microscopy, the limits of high tech hyperbole and how scientists cared for the organisms they studied and how makers cared for each other through their tools.

Final Lab From A Chip kit in packaging with live algae, Interspecies Gaming handheld lighting stage for Foldscope, Foldscope kit, Micro-environment making kit, Critical Kits Manual with details of ‘artworks’ ie research projects, and a Bio-Trumps card game as literature review

Practical Workshops and Praxis

Algae Bio Plastic Lab Workshops with Origami by Hwa Young Jung

How that research and subsequent method played out in my practice as an artist after my thesis can be seen in my recent Algae Bioplastic Lab project. For a residency at METAL Liverpool, I wanted to explore bioplastic as a material which I had started using in the research. Essentially I wanted to explore how the concept of innovative biomaterials was being used to address the crises of fossil fuel use - in particular commodity production’s dependence on petroleum based plastic and the increased toxicity of plastics in the environment. My experience was that a good deal of excitement, development and hyperbole surrounded the idea of bioplastics as a way to replace petroleum based production. When I actually made some bioplastic myself, using the excellent resoures of Materiom I felt exilerated that I could make a ‘new’ material from remarkably simple ingredients and processes with the knowledge you were working toward a non petroleum future. Much of my art practice involved discovering emerging democratised making projects and instructionals and then building participatory creative workshops around them. I also took part in a workshop run by STEAM house at Birmingham City University aimed to develop artists, designers and makers use of biomaterials into realised products, businesses and enterprises. However once I tried to develop prototypes into a volume of consistent material to make something - in my workshops case bioplastic origami I quickly started to realise the limitations of the biomaterials in terms of tensile strength and other qualities, like resistance to water. From there it quickly became clear that I could not imagine what kind of biomaterial could replace the materials used in my own wheelchair wheels or laptop. It made me understand how far we were from agency at the actual scale and nature of the forces of production at work in the world. The embodied study of making with people became an opportunity to understand the limits of materials and the actual needs of human life. Very quickly you start to wonder how plastics and rubber is made and consider that rubber and petroleum plastics are already biomaterials. Firstly, they are in the sense that they originate from biological life and biological processes but also that their use is bound up deeply in relationships of a ‘web’ 6 of human and extra human nature and life.

Instead of showing people an elaborate artwork ‘about’ bioplastic and then discussing it, I made a kit and set of resources for people to make their own bioplastic sheet material and experience it’s limitation. Much of media accounts of responses to climate change is full of innovations and initiatives to be ‘sustainable’. But it’s easy for these projects to just become reassuring stories and performances of prototypes that never end up making a difference at any kind of scale. By making your own bioplastic you appreciate the constraints and limitations of the material. Taking part in the workshops making together, critical or otherwise, you can start far more complicated conversations about how to make the world differently than just a simple celebratory how-to. The hands on making of bio plastic, forces you to understand the labor time necessary to make anything, which we normally are completely alienated from in the world of instantly accessible commodities. From there you appreciate the orders of magnitude of change and development necessary to make any real difference in the world becomes not an abstract concept but obvious and something you can experience. Unlike many maker related workshops that legitimately share the knowledge, what I learned from my research and the traditions of analysis in Science and Technology Studies was that these kind of workshops can also be used as critical interventions in learning and understanding the material nature of our world. Biomaterials cannot simply be swapped out for petroleum ones, it requires a much bigger political not technical process and project.

At the moment green politics is in danger of reducing itself to a form of moral panic and eco austerity. This is accepted by some of us who might appreciate the scale, immeadiacy and impact of the climate crisis, especially if we have the capacity and social capital to do so. But for others, in reaction, this can be vociferously rejected. What’s absent is a more universal political project, one that is not pure emergency and austerity but also one that does not fantasise how we can grow our way out of the situation. This project must be built over time and with care and involve large amounts of people across the class stratifications of modernity. We must begin taking back some kind of democratic control of production if there’s any hope in mitigating the effects of the changes in climate on the capitalist world-system.

The key thing for me, based on my research and experience of the maker movement was not the easy access to technology or a celebration of modernity’s profound technical abilities, or making a new generation of progressive engineers, but the actual democratisation of technical knowledge and the forces of production. Making things together at a small scale has a political potential, the main claim I made in my research. Looking back, I think I must stress that it is only a potential and a tactic amongst many; the rest is the hard work of organising people to legitimise a political project that reorganises production democratically and is not just a politics of austerity.

This is how I implemented the methods of Interleaving and kit making. The Bioplastic kits are a form of group education and a method of critique. It does not fetishise the idea of a lab but the commission paid me to develop and deliver some online resources and workshops that can be repeated and distributed locally and in-house instead of exhibitions and artworks. It is meant to be a critique of the utility of artist residencies and a model for professional practice. How to make this model into a sustainable income for artists and organisations is something I’ve been thinking about for further research that is like a more critical version of the work Steamhouse did with Materiom for the BioBox project I participated in 7.

The Biobox developed by Materiom with Steamhouse in Birmingham and Distributed Design coordinated by Fablab Barcelona and the Institute for advanced archistecture of Catalonia (Iaac). ‘This project looks to actively challenge our consumption habits through education and develop responsible design as a key component when measuring successful design.’ Image credit: Jackie Pease

To do so called socially engaged work, be that through a quite specific and emergent ‘art-science’ practice like mine, creative social science research, or much longer and richer traditions of community art, craft, making and activism, it can help to understand the complexity of the social process you are part of. Thinking of this using the word assemblage means you can understand the social world as not just what’s happening there in the immeadiate context and moment, but the long tail of historical, material and ideological conditions of the kind of situation, the practices, and the class positions of participants and artist or researcher. Any method of knowing has to get deep into the complex layers of that process and how it might interact with others and how it all gets assembled together as an object, phenomena or distinct social group. Assemblage is a term used by a range of social scientists and critical theorists including Félix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze 8. To understand the assemblage you are part of or working in, you have to interleave many different layers of things and processes, reading between and across different layers, traversing different landscapes of knowledge and experience. With this messy assemblage perspective, objects, practices and institutions, even scientific facts are not ‘natural’ things-in-themselves but historical accomplishments.

Further to that, you can become critical and conscious of your own role in that accomplishment, that social process, and be aware of the implications, presumptions and often obscured political committments you might have when you try to engage with something. In my approach, and in the conclusions of my thesis, you start to critically understand not only the possibilities of something, which can lead to utopian overstatements and hyperbole, but the real material constraints of what you can and cannot do, based on the historical terrain and conditions of what you’re doing . In the end you start to think of what you do as an artist, educator or social scientist in strategic terms. What do you want to do in and with the process and how to get there?

Strategy and History

Thinking of art practice or indeed any practice as a strategy for understanding and working within society and ultimately changing it, was an unexpected result of my research into critical making. It’s liberatory as it makes you acknowledge what you really desire for a project: where do you want to get to with it? But as soon as you consider strategy you must acknowledge not only that there is a path to some kind of desirable objective but that it is overwhelmingly outnumbered by multitudes of paths that could lead to compromise and failure. In my thesis I used the work of biologist Stephen J Gould who understood biological and social evolution as not a linear progression of progressive improvements ‘selected’ by competition but a vast series of ‘decimation’ 9 as different communities of organisms have their time and then disappear from the historical record. From this more pessimistic perspective what is difficult to explain is not what drives things to change but what keeps things together. What practices did people have to do and keep doing to reproduce and maintain something? What historical conditions aided that process? How did we become dependent on extracting coal and oil for cheap energy and materials?

Historical Terrain

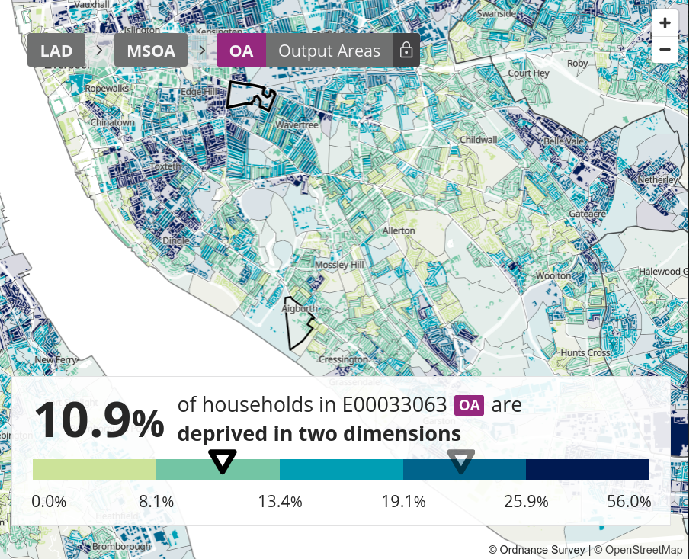

Image from Office of National Statistics Census 2021 data comparing Household deprivation between METAL, the location of the AlgaeBioPlastic Lab workshops in the Wavertree area, the source of secondary school participants in the project and my own postcode in Aigburth. ‘Deprived in two dimensions’ refers to any 2 dimensions of 4 household characteristics: Education; no one has at least level 2 education and no one aged 16 to 18 years is a full-time student, Employment; any member, not a full-time student, is either unemployed or economically inactive due to long-term sickness or disability, Health; any person in the household has general health that is bad or very bad or is identified as disabled or assessed their day-to-day activities as limited by long-term physical or mental health conditions or illnesses are considered disabled, Housing; A household is classified as deprived in the housing dimension if the household’s accommodation is either overcrowded, in a shared dwelling, or has no central heating.’

The reality of how our desire to know and the extent to which we can intervene in the world, through science or art, is constrained by the particular historical conditions and terrain of our situations. This is something I think is often made absent from our received folk ideas of art practice and art education. Certain narratives of popular art and cultural history seem to suggest artists are innovative outsiders and heroic leaders of counter culture, leading symbols of new possibilities for changing society and culture. It is much more useful to understand that artists are produced by the dynamics of social change, not to say they are unimportant, but that they are attuned to the feelings of the time, rather than driving it. Again using Williams’ most enduring concepts, artists tend to be incredibly sensitive to the currents of structures of feeling 10. Perhaps under the pressures of a political economy of art where artists must be always developing their practice to compete in a highly precarious industry of attention, to be seen as important or relevant, drive us to overstate the possibiliies of our practice in it’s own terms. Understanding the constraints of how art can point at problems might help artists come together and connect to wider movements.

I claimed in my thesis that using this method could be used politically, in the context of crises like climate change. I claimed that this kind of art practice was building up people’s critical understanding of microbiology or sustainability. Since then I think I was thinking more about possibilities over constraint, perhaps to be competitive in the market economy of the workshops that sustained my professional practice. These workshops are taking place in often unacknowledged secluded social conditions - there is nothing in the kit that considers how different people might respond. It assumes a level of social capital to engage with it and presumes ‘non-scientists’ means ‘everyone’. There is a common, well-meant, implicit assumption in kit making culture that the democratising kits, often painstakingly documented in accessible language, are ‘for everyone’. But clearly not ‘everyone’ will use the kits in my Algae Bioplastic project or take part in the workshops. Only a very select if not a self-selecting group already open to the idea of alternatives to plastic, or students selected by a local school actually use the kits. In my research I realised that what is in a kit, what makes it ‘work’, is more than just a bag of components and good easy to read documentation, but what is ‘hidden’ beyond it; the users capacity to use the material and gain something from the experience. The kit is not a self contained thing but part of a social process. Everything in life experience, class, race and gender position affects how people use any kind of kit or ‘educational’ resource. How kits democratise things has to consider the hidden dimensions.

In my research I spent long sessions with participants to ‘build’ that capacity. I had to realise my assumptions and the experience of my collaborators and we made that capacity together - we interleaved our respective experience and capacities. This sounds complicated and I could elaborate this in Deleuzian terms. But it’s also obvious to anyone, critical theory isn’t necessary to understand that to work with people you need to understand their needs, feelings, material interests and experience, assume nothing, be generous and patient and bring them alongwith you. Everything that we all do everyday. To really be an Interleaving Practitioner I would need to do the harder work to develop these kits with the participants and this unfortunately was beyond the scope of a small residency programme. The investment of time required for this kind of work can only be dealt with institutionally and in the current moment this is by far the biggest restriction. Not only are institutions starved of resources for time, this kind of work is not really valued but more than that people don’t have time to develop their capacity beyond basic survival.

Reflecting I would say that my claims are actually symptomatic of alot of art-science and so called ‘socially engaged’ art practice, also known as ‘relational art’ 11. It can become a kind of micro politics that claims that by ‘changing minds’ through alternative experiences we can ‘change the discourse’ and ‘raise awareness’ around a progressive topic. It reminds me of something else Williams called a long time ago, militant particularism 12. For Williams, he was describing how a political project focussing on a particular set of demands in a particular situation; miners in a specific community in Wales, could then be articulated into and connected to a progressive universal demand for meaningful sustainable working lives that might resonate with people with different often incommensurable and even reactionary perspectives. Much of my art practice and others has an impressive amount of innovative militancy of the particular, but an inability, or perhaps something more like a structural constraint, to articulate it beyond its microscopic particulars into more universal demands or progressive projects that a wider pubic could engage with. I quoted political theorist Jeremy Gilbert in my thesis, who critiques so called ‘relational art’ which ‘socially engaged art’ is arguably a part of, but I dont think I have really developed a convincing response to it either in my thesis or my practice since.

The problem with most ‘relational art’ is that it absolutely exemplifies the tendency within both cultural and political radicalism to engage in ‘tactical’ interventions which simply have no social or political effect, to the extent that they become isolated enclaves within which a certain set of ideas or experiences can be preserved and reproduced, while having no discernible impact on anything outside of themselves. Experiential laboratories they may be; but an experiential laboratory with no ability to publicise its results, with no ‘strategic orientation’ to the outside and to the future, remains nothing but an enclosed territory and a depoliticised space 13

This may not happen just because artists get lost in their own little specialist worlds, or have limited sensitivity despite art education developing sensitivity perhaps most of all. If we think on a more abstract level, the historical conditions of the social process and terrain in which they work have very specific constraints. Complex structures of class society make it difficult to connect, or even be aware of, how the militant particularism and micropolitics of most art practice fails to be meaningful to a more universal public; you end up endlessly preaching to a sub set of the converted. As an educator you need to have a strategic orientation to dealing with that problem.

Making something with and for a very specific group of people, can attempt to avoid the problem of particularism by being explicit about the limited remit and objectives of the project, which I feel I did to a degree in my research. On reflection I think many projects also have to have some hooks and handrails to relate it to other groups and other wider political or social projects if it wants to be seen as relevant or important or used by anyone. It’s important to note how much artists workshops, primarily seen as important sites of engagement, are leveraged to justify the social utility or legitimacy of art practice or art organisations, so what happens in them and what the strategic desire for them is, does matter, and perhaps to a much larger degree than it might seem. If we want art practice to change the world, increase people’s capacity to care, to experience joy and empowerment through democratically distributed knowledge, then we need to develop methods to develop our strategies.

These may not have to be new and innovative, there’s a whole tradition of engaging work, but they need to be sensitive, understand their terrain, assemblage and be open to criticism. They need investment of both time and resources and institutions who support critical thought, which is increasingly under threat when certain kinds of knowledge is seen as valid and others not. METAL Liverpool were exemplary in regard to investing in time for the Algae BioPlastic project, but these opportunities, like my own PhD scholarship which made my research possible are rare. At the same time we have to be aware that the institutions of expertise and funding are increasingly part of a social process understood by various publics and citizens as losing both legitimacy and relevance. We have to think what we really want to do, and do the harder work of how to get there and make sure that whoever benefits from it is for the many, and not just the few.

You can download the thesis here.

-

Taylor, K. and Rohrer, D. (2010), The effects of interleaved practice. Appl. Cognit. Psychol., 24: 837-848. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1598 ↩

-

Harvey, D. (1996) Justice, nature, and the geography of difference. Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell Publishers. ↩

-

Dalziel, R. and Winterburn, N. (2016) ‘Critical Kits Re-Dock’, Re-Dock. https://re-dock.org/critical-kits/ ↩

-

Jones, N. (eds) et al. (2016) Critical Kits And How We Use Them. First. Torque Editions (1st ser.) ↩

-

Ratto, M. (2017) ‘The Critical Experience of Making: Interview with Matt Ratto La experiencia crítica del hacer: Entrevista a Matt Ratto’ and Hertz, G. (2012) ‘Critical Making - Hertz’, Critical Making Concept Lab. https://www.conceptlab.com/criticalmaking/ ↩

-

Moore, J. W. (2010) Capitalism in the Web of Life ↩

-

King, S. and Powell, Z. (2021) BioBox STEAMhouse X Materiom, BioBox STEAMhouse X Materiom. Available at: https://distributeddesign.eu/awards/entries/biobox-steamhouse-x-materiom/ (Accessed: 12 August 2021). ↩

-

Buchanan, I. (2021) Assemblage Theory and Method. Bloomsbury Academic. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350015579. For me Buchanan’s reading of Deleuze & Guattari is much more useful than the original texts which I find dense and unwieldly. ↩

-

Gould, S.J. (1990) Wonderful life : the Burgess shale and the nature of history. London: Hutchinson Radius. ↩

-

Williams, R. (1975) The long revolution. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ↩

-

Bourriaud, N. (2002) Relational aesthetics. Dijon]: Les Presses du Réel (Collection documents sur l’art). ↩

-

Williams, R. 1995 Social Text (no. 42, Spring), 69-98. ↩

-

Gilbert, J. (2014) Common Ground: Democracy And Collectivity In An Age Of Individualism. Pluto Press. ↩