The Kits Just Keep Coming!

reference to a recent advertorial newsletter from proto-pic

Thoughts on kit cultures for the #Critical-Kits symposium

A while back I attended Laura Pullig’s Nature & Technology symposium which I talked about before and one of the things that came up was how Neil Winterburn, Laura and I noticed everyone seemed to be talking about ‘kits’ and this was the beginning of what’s become the #Critical-Kits project.

8 years previously I remember discussing with the Owl Project in 2008 how they could sell their iLogs in the FACT shop but as a kit with a workshop to make them, well before the maker meme really had any traction. Arduino’s where not really out there; Steve Symons had to build his own platform ‘muio’ to help make the technology based work the Owls required.

Artists making kits or building systems of some kind now seems to be a standard practice for those using technology and we wondered what was behind this and what opportunities or problems this might raise for artists.

Neil Winterburn jokingly tweeted recently that I’d tied myself to the mast of maker culture, referring of course to Turners’ hardcore experiential research for his storm studies and paintings.

In preparation for #critkits @cheapjack spent the past 5 years tying himself to the master of maker culture @DoESLiverpool #weeknotes

— Neil Winterburn (@onthepennines) November 29, 2016

I’m not comparing myself to Turner here, (and quickly tweeted back a bad github geek pun to try make that clear!) but it’s coincidental how Turner has always been for me to be a pre-cursor for ideas around ‘modern-ness’ in art.

His sceptical interest in emerging 19th century science & technology, and friendship with people like Mary Sommerville has always fascinated me and although a classic romantic ‘auteur/artist/genius’ seemed to be trying to access an underlying reality of light and experience, his research efforts travelling and embedding himself to capture this ‘experience’ of landscapes legendary.

I do think that many artists interested in using technology often try to build deeper relationships with the wider technical cultures around it; and this is a kind of ‘mast tying’ and a pretty standard form of artist’s research.

Equally I think there is a tendancy to refer and re-present (rather than represent) elements or speculations around a technology or scientific discovery as an artistic response and in some case as a general form of practice. I think this is ethically suspect and can lead to ultimately ineffectual work; the classic is

- Speculate on the implications of blah blah

- Start a dialogue around blah blah

- Taking blah blah as a starting point the artist uses a fictional meta narrative alongisde the real blah blah

Responding to a technical culture through research or some form of participation in that culture even on a superficial level, rather than using technical facts out of context as a subject I think leads to more complex work that can be built upon

When I was interested in sound based art I tried to engage with that culture through SoundNetwork and began to meet artists like the Owl Project. Working with them was a key moment for me, their practice of research and independent making and building their own ‘systems’ for making their work made complete sense.

They did not just ‘use’ technology they made themselves part of it’s culture through designing and building; to generate a ‘kit’ for themselves to further their work. The muio framework, performances and transparent methods for how they made things embodied their practice. But they did this with a genuine admiration for technical culture not an exploitative intervention approach.

I will never forget that when developing their MIDI Sound lathe, a pre-cursor for their massive Flow installation they were all incredibly excited about a research visit to a wood turning festival: it showed a real love for craft and care and a regard for community.

I think that’s at the core of artists using or referencing kits: building a system to make your work can embody not just a process but an ethos and it can become a form of credential. Building a ‘kit’ or a system can also be part of a critical response to the proprietary tools we are sold as artists. The tools we use are often the tools we are allowed to use; dig a bit deeper and you can find things like Wireshark, Re-decentralize, Inkscape and Kitnic. In the same way as artists use ‘labs’ it’s a kind of validation for creative work; it proves a use-value for your practice.

I also think the urge for artists to engage in cultures outside of art, refers back to the idea of ‘natural philosophers’ before the term scientist was coined from artist

I recently ran a ShrimpCraft workshop with PlayfulAnywhere on the banks of the Leeds/Liverpool canal and found a print of Turner’s study of the canal just 5 minutes along from our workshop location which led to an idea for an unsubmitted proposal for Domestic Science.

Taking the ‘critical making’ idea, I wanted to frame it within this history of late 18th century notions of ‘natural philosophy’ (when art and science where ‘closer’ and canals a major distribution network). It also echoed my experience involved in the Open Source Swan Pedalo community, also initiated by re-dock and my work with Amanda Steggel and Elizabeth Weihe for Currently and Co-Tidal.

I proposed using this now redundant distribution network, the Leeds/Liverpool canal to explore a kind of ‘slow-manufacturing’, as a response to artists involved in kit and maker cultures. Make kits that carefully include the contexts for their use within both their design and documentation; any making would be connected to contexts of communities whose relationships we would develop along the canal’s path. There would be a kit per ‘node’ along the canal, a node being a context about local industry which would contribute to Adrian McEwen’s fascinating mapping of re-distributed manufacturing a project contextualising manufacture and the nuances of local supply chains.

In many ways the logical implication and next step of kit and maker culture would be for makers and artists to begin to manufacture things and start making and distributing at ‘scale’. A few factors meant this slow-manufacture idea remained a proposal but all of this kind of thinking drifted into the #Critical-Kits symposium.

This was another great opportunity to work with Neil Winterburn and re-dock who I’ve always thought of as peers and representatives of art & technology done right, with a focus on community without losing critical elements.

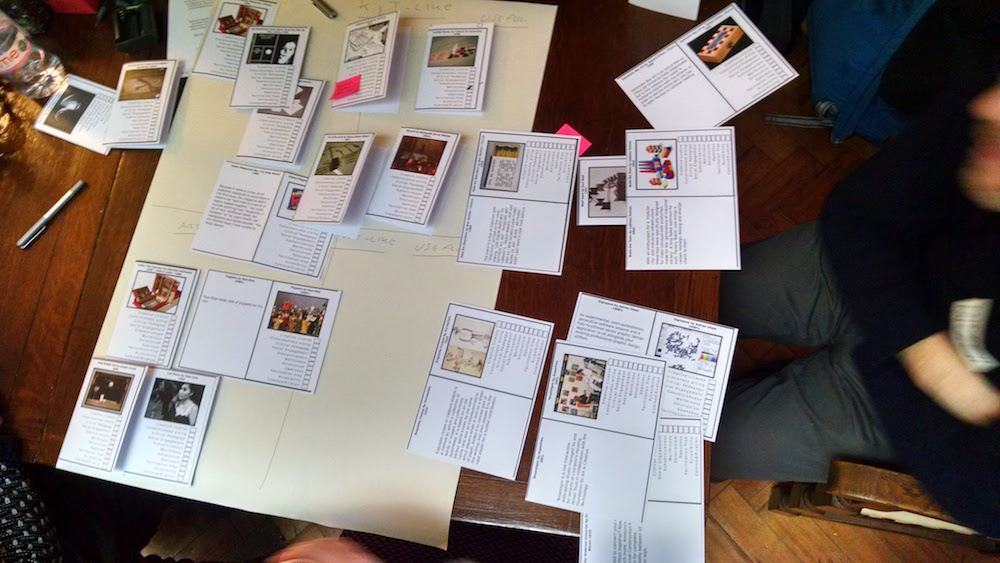

For the symposium we wanted to refer broadly to a culture of critical thinking and a culture of kits and apply them to artists who work in participatory art and technology to reveal some opportunities for the better documentation and so communication and ultimately validation of that kind of work.

You can get a full explanation here

One thing that came out of it for me is that some kits are not necessarily fulfilling the implications and opportunities of mass distribution: in some ways they just embodied a complex practice or narrative around a participatory project, community or technology use. In a sense the kit has the potential to tell a story better than a youtube video or a blogpost.

We also wanted to show that there was already an artist tradition of taking ideas from kits, manufacturing and mass distribution. I would have liked to have dug into technical culture’s traditions and precursors a bit more which I think we can do at future Critical Kit events.

Finally what I’ve been reflecting at Critical-kits, Maker Assembly, re-distributed manufacturing and that idea of slow-manufacture on the canal and the many other growing, exciting making-culture community activity out there, is that one of the reasons many of us are able to develop electronic kits and open source things at all is to do with macro economics and crucial ‘price points’ not to mention the privilege of knowledge or time to generate it.

These things put the degree of control you have over what you do into perspective: Can you only ever really respond to the market or can you start to influence it?

As influential as Maker culture is and it’s integration into everything from school, libraries, manufacturing, the high street and academia is it ever really more than another specialist subset niche market dependent on vast volumes of production and e-waste to get tools and components into the hands of enough people? And does that make us really no more than users, or at best shop stewards with limited powers and not the system administrators of our lives, societies and futures given their dependance on technology?